Christopher Tanner, [. . .] has found the heaven above by looking below, the twinkle in an eye that does not blink

— Carlo McCormick

Nude 3

2004

Pastel on paper

17 x 14 in.

Nude 5

2004

Pencil and pastel on paper

17 x 14 in.

Nude 15

2005

Pencil and pastel on paper

17 x 14 in.

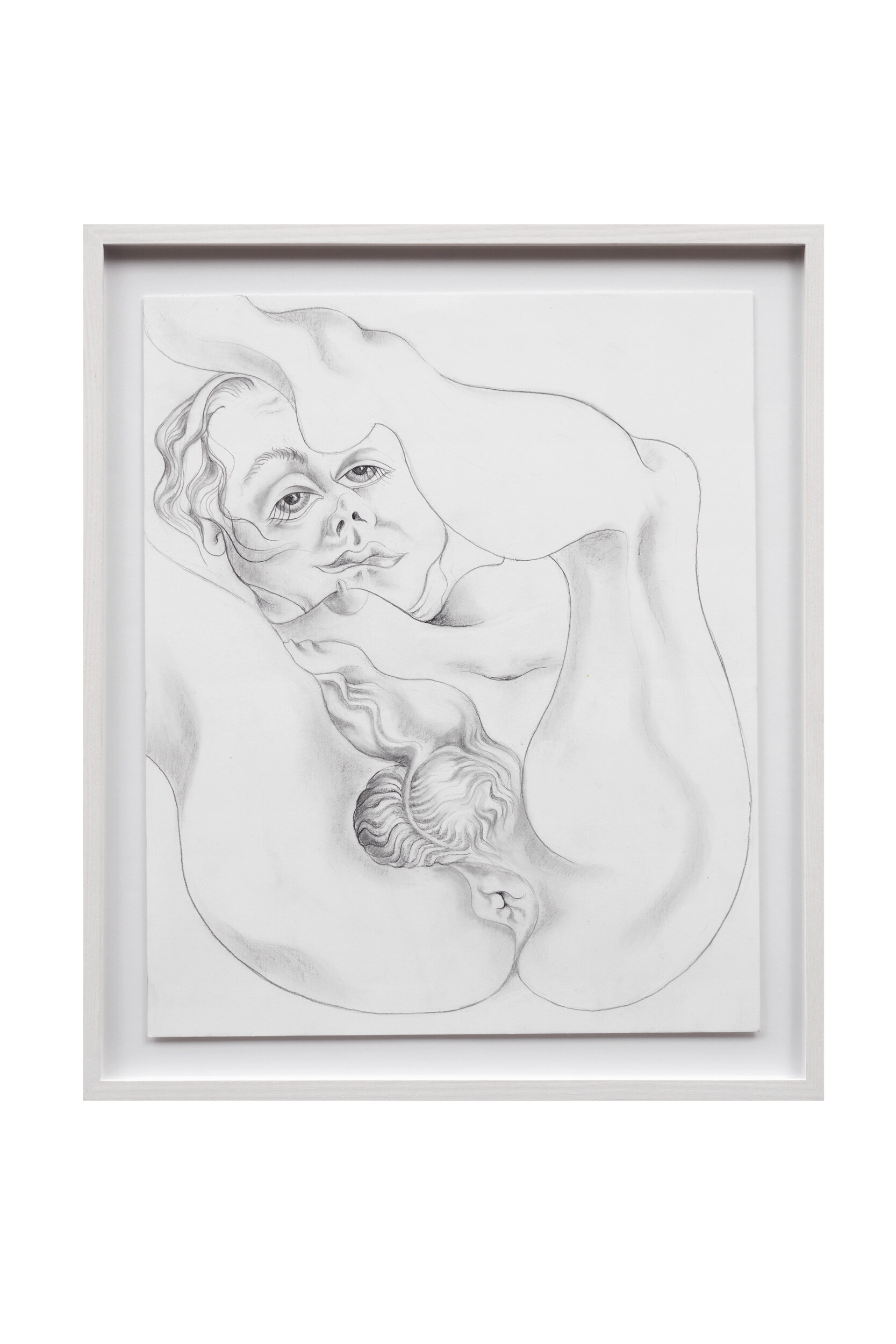

Nude 17

2015

Pencil on paper, framed

17 x 20 in.

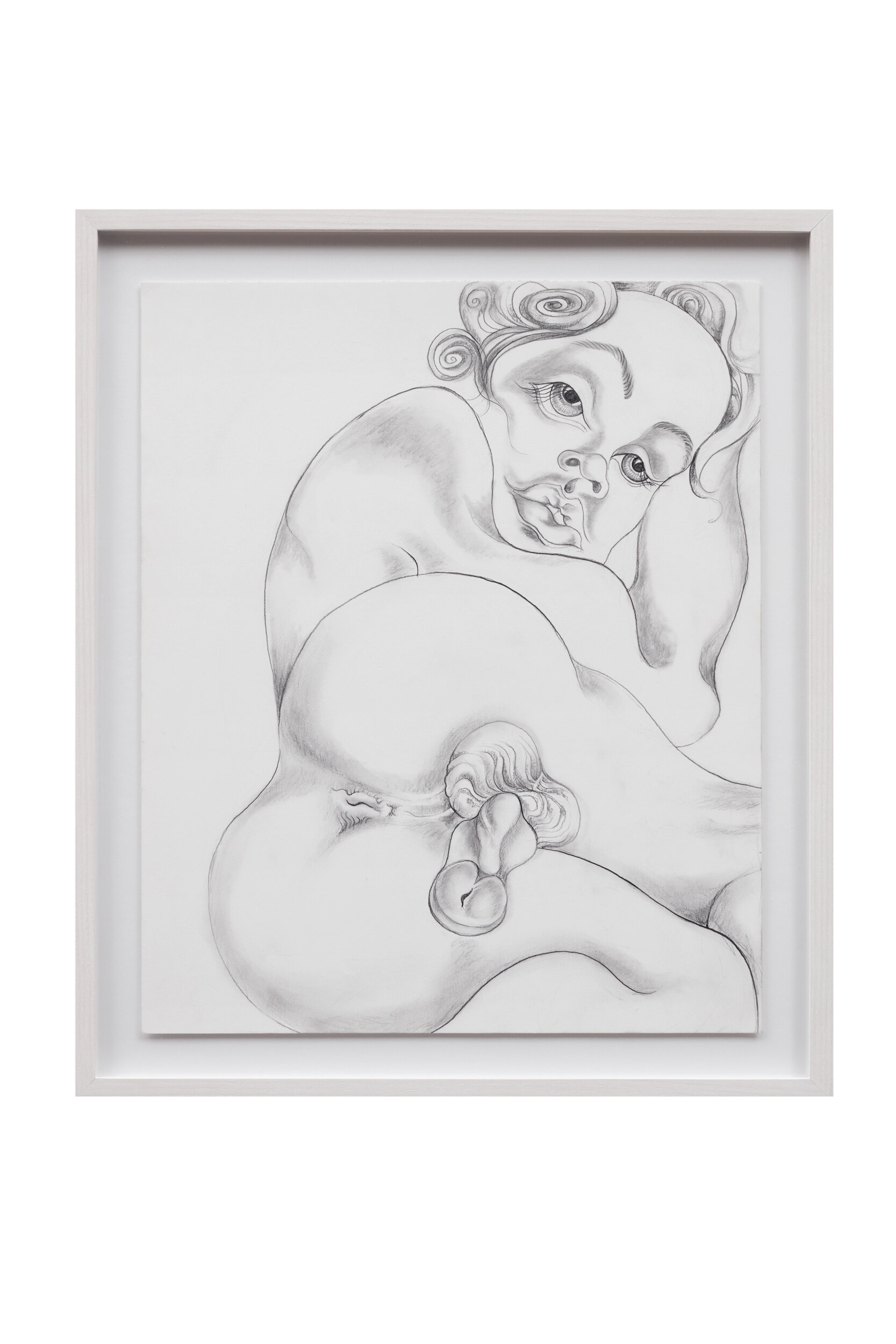

Nude 18

2015

Pencil on paper, framed

20 x 17 in.

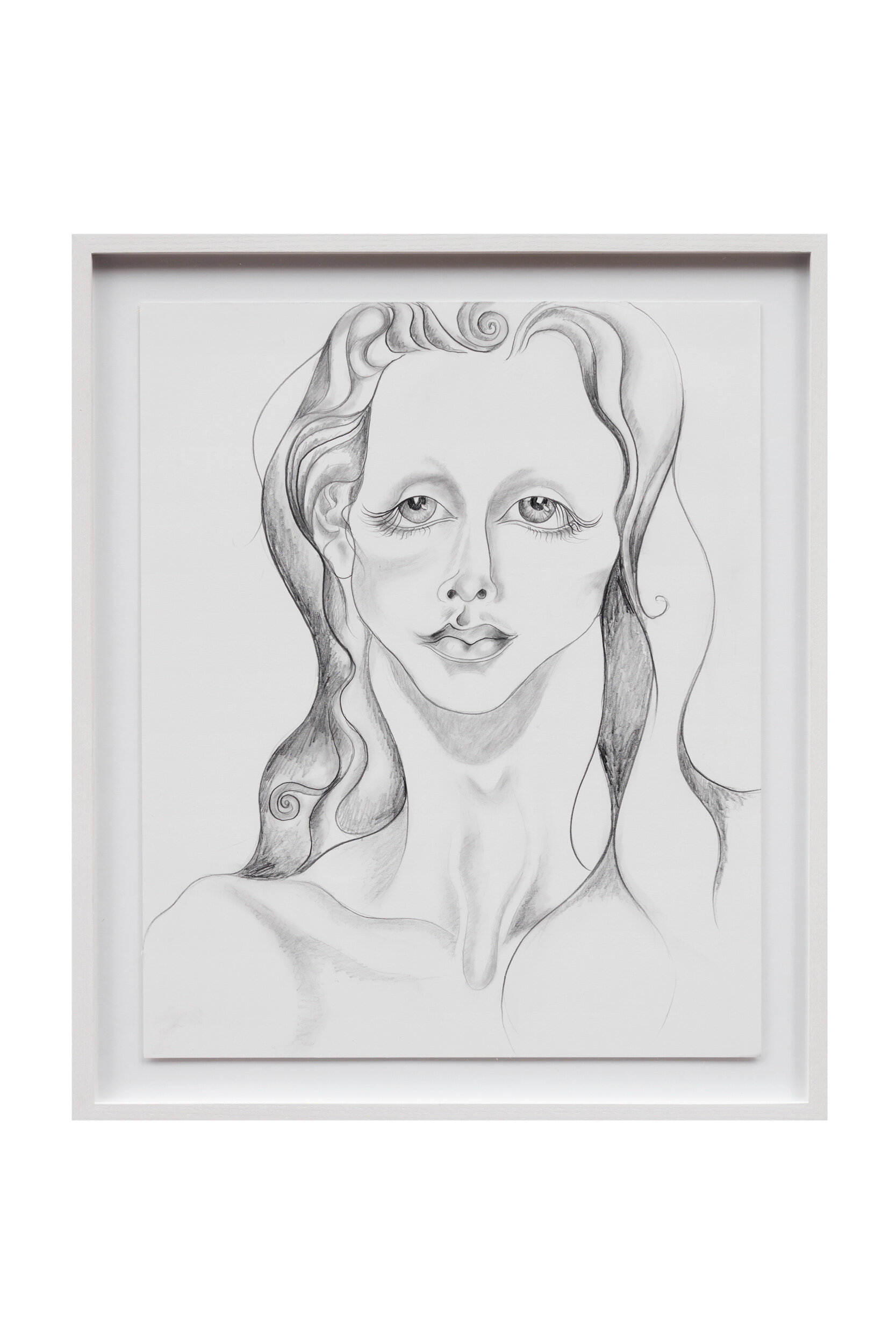

Nude 19

2015

Pencil on paper, framed

20 x 17 in.

Nude 20

2015

Pencil on paper, framed

20 x 17 in.

Nude 21

2015

Pencil on paper, framed

20 x 17 in.

Nude 22

2015

Pencil on paper

34 x 14 in.

Nude 23

2015

Pencil on paper

34 x 14 in.

Nude 24

2015

Pencil on paper

34 x 14 in.

Nude 25

2015

Pencil on paper, framed

20 x 17 in.

Nude 26

2015

Pencil on paper, framed

20 x 17 in.

Nude 27

2015

Pencil on paper, framed

20 x 17 in.

Nude 28

2015

Pencil on paper, framed

20 x 17 in.

Nude 30

2016

Pencil and pastel on paper, framed

45 x 20 in.

Nude 31

2016

Pencil and pastel on paper, framed

45 x 20 in.

Nude 33

2016

Pencil and pastel on paper, framed

45 x 20 in.

Nude 34

2016

Pencil on paper, framed

20 x 17 in.

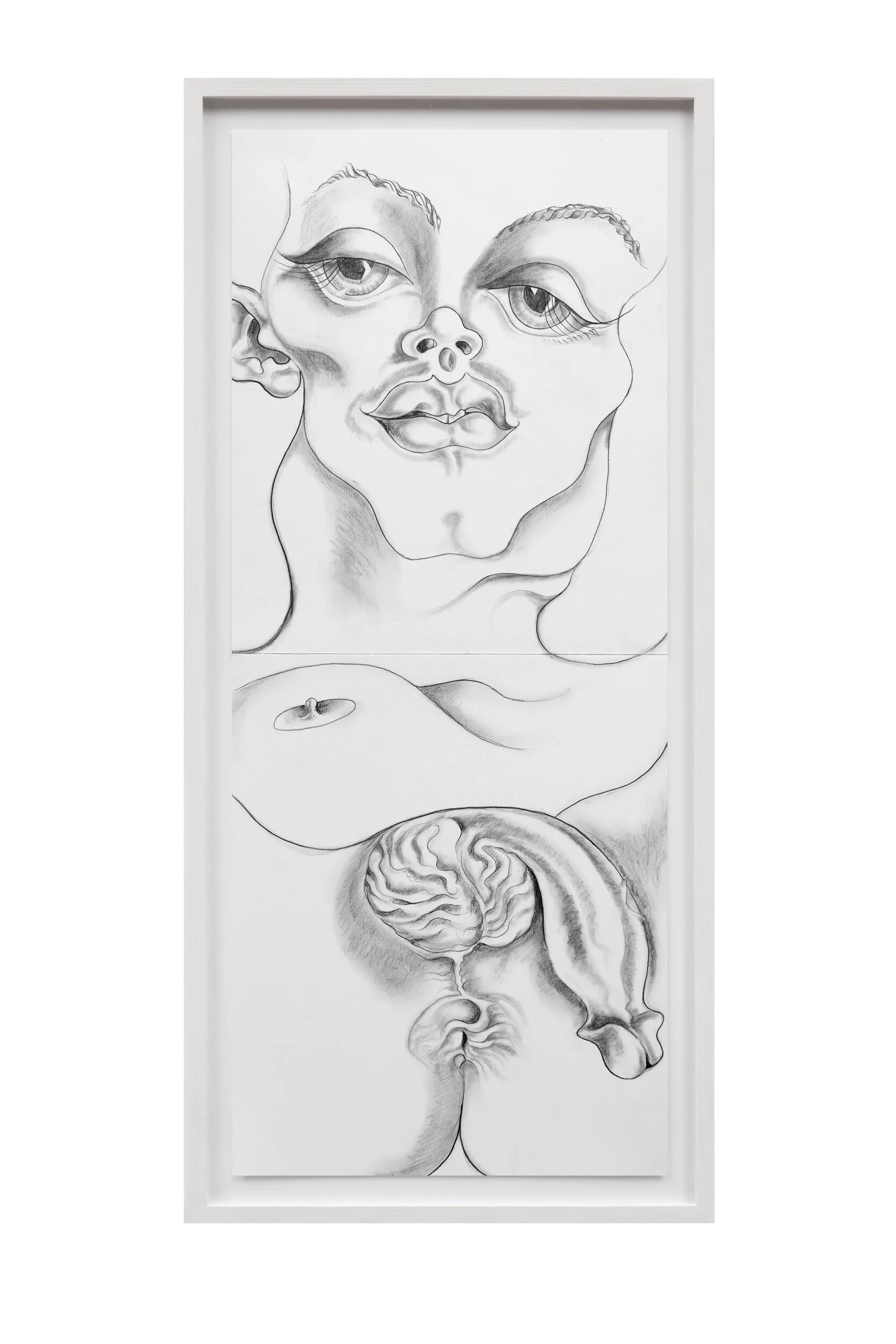

Nude 35

2016

Pencil on paper, framed

37 x 17 in.

Nude 36

2016

Pencil on paper, framed

37 x 17 in.

Nude 37

2016

Pencil on paper, framed

37 x 17 in.

Nude 38

2016

Pencil on paper, framed

20 x 17 in.

Nude 39

2016

Pencil on paper, framed

20 x 17 in.

Nude 40

2016

Pencil on paper, framed

37 x 17 in.

Nude 41

2016

Pencil on paper, framed

37 x 17 in.

Nude 42

2016

Pencil on paper

17 x 14 in.

Nude 43

2016

Pencil on paper

34 x 17 in.

Nude 44

2016

Pencil on paper, framed

17 x 37 in.

Nude 45

2016

Pencil on paper

17 x 14 in.

Nude 46

2016

Pencil on paper, framed

20 x 17 in.

Nude 47

2016

Pencil on paper, framed

37 x 17 in.

Nude 48

2016

Pencil on paper, framed

31 x 20 in.

Nude 49

2016

Pencil on paper, framed

20 x 17 in.

The I of the Beholder By Carlo McCormick

All that glitters may not be gold, but there is room in aesthetics for the ersatz that sparkles and beguiles all the more for its tawdry materiality, for the intimations of the imitation delivered in surfeit, anointed by the obsession of craft and made transcendent by the suspended belief of impersonation. Christopher Tanner’s radical embroidery is of just such a cloth, improvisations of importune immediacy delivered with ebullient excess. His is a daft kind of outlier art let loose from the sobriety and seriousness that restrains so much of fine art, but part of a wilder tradition of over-the-top ornamentation that lies like a frivolously frilly fringe on the margins of high art’s dour raiment, altogether a historical other that taken together constitute a crazy-quilt of ulterior beauty. Tanner’s tapestry paintings are the antithesis of minimalism’s primary structures, eschewing the reductive while celebrating the secondary, tertiary, unnecessary, and incidental as manifest of new meanings beheld in the confluence of myriad details. Little things matter, and too much is never enough.

Surface as form, manifold and mesmerizing, an erotic rapture of unfettered hedonism without apotheosis or climax (or is it rather ceaseless orgasm?), Christopher Tanner’s vision is oceanic, expansive in a way that intimates depth as it belies it, the horror vacui subsuming perspective and obviating distance in the gluttony of indulgent fancies. Exaggerated and ostentatious yet without the irony of camp, affected (though sincere and unpretentious) to the point of extreme effect, Tanner makes art that is queer for its outré difference, sexual preference, and effeminate opulence. This theatricality, the elaborate staging of desire as a kind of lowbrow glamour, is at once a historical lineage and startling contemporaneousness within this work. It is central to the downtown vernacular of New York style, the DIY modified thrift store fashions of the nightlife, the amateur pageantry of its performance art, and the low-budget exoticism of its transformative art—running particularly strong in the East Village and suffusing the sumptuous and seductive swank of artists like Jack Smith, John Torreano, Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, Ethyl Eichelberger, Rhonda Zwillinger, and Tanner’s direct mentor Arch Connelly.

Art that flowers in unorthodoxy, whose blooms are too florid for the eyes and fragrances cloyingly sweet, surges past the bounds of decorum into the effluvia of deranged décor, and in such a leap dances close to the cultural taboo we call kitsch. This is no mistake, no lapse of judgment but rather quite deliberate. At once a sensibility and a strategy, the mannerisms of kitsch have constituted a forbidden path out of the dialectic orderliness of modernism. Chris Tanner is utterly earnest and reverent in his embrace of the gaudy; it is a matter of registered in the eye. What we do not see, where the sun doesn’t shine and society holds as private as well as somehow shameful, has been excised from our language regarding beauty and the divine. There, unspeakable and out of sight it has far from been out of our mind, buried deep under the social armature of etiquette it has lodged in our collective imagination, slipping out through our bawdy humor—or if you’re Freudian through all manner of pathology—and finding rare voice in a chorus of heretic hymns to this forbidden passage, from the vulgar yet fantastical marginalia drawn by monks on the borders of medieval manuscripts to the preoccupations of Georges Bataille and his L’Anus Solaire. Christopher Tanner, a total top who finds his salvation through submission to the asshole, has found the heaven above by looking below, the twinkle in an eye that does not blink. Art for him, as with so many before, is a sublimate act of love. Unusual, and perhaps shocking for some, he is not alone in this regard, preceded in a posterior poetics of this inner sanctum by the likes of John Waters’ Twelve Assholes and a Dirty Foot, and a remarkable book by Allen Ginsberg’s longtime lover Peter Orlovsky, Clean Asshole Poems. Sadly overlooked since its publication in 1977 and largely dismissed not just for its subject matter but because Orlovsky’s genius was illiterate, and he couldn’t spell, it is a paean on the order of Tanner’s, and the great beat Gregory Corso’s introduction to the book speaks well to the passion of Tanner’s work: He hails the human asshole as divine — He offers humankind an anatomical compassion for that bodily part long-maligned, shame-wracked, and poetically neglect. Keep it clean in between is a golden define of self-respect. The angel without wings is with asshole a reality. The angel with wings is a painted thing, a dream. The dual asshole: bucolic and sexual. What comes out, he believes, aught benefit the fields not the seas, aught fertilize not pollute — What goes in, he lauds as a variable of sex not solely of homosexual kind — The lovers of callipygian joy are universal. heart and soul even as intellectually it is also pulling our leg. In a culture where the spiritual is bound up in a puritanical refusal of pleasure, Tanner reminds us of an ecstatic sublime. Here kitsch is not simply some failure of taste, as it is in so many other garish things people take for art, but a fabulous indecency with a specific antagonism against propriety. Be it a personal proclivity or a more political polemic, kitsch resides in the pluralism of post-modernism as a balm for the chafing constraints of refinement. That is, for all its indulgence it is ultimately an oppositional tactic set against that great modernist champion Clement Greenberg’s proclamation that for every avant-garde there is a rear guard, and that rear guard is kitsch.

Before it became such a loose adjective for all that is culturally reviled, kitsch represented a sham impersonation of the spiritual, born at the time when religious artifacts like crosses were no longer the sole domain of craftsmen whose hands were guided by divinity but mass produced on the assembly lines of industrial age manufacture. Tanner’s transgression then is a kind of mystical sin, that he worships what we shun, a false god of superfluity versus purity. This is gothic multiplied and maximized to a rambunctious rococo, handed down like the heirloom family jewels since the 12th century, when Abbot Suger ushered in the gothic era at St. Denis with a profligacy of gold, silver, luridly colored stained glass, sapphires, rubies, and whatever other jewels might sparkle most to amplify experience through architectural splendor and relate the immaterial through the most material of terms. Or as he inscribed on the very portal of his cathedral: “All those who seek to honor these doors, marvel not at the gold and expense but at the craftsmanship of the work. The noble work is bright, but being nobly bright, the work should brighten the minds, allowing them to travel through the lights.”

Finally, since Christopher Tanner’s adoration is of an entirely different order, let us revel a bit in the unorthodox object of his affection—the asshole. Describing this oft overlooked and systematically despised bit of anatomy we all share, Chris told us they are “like heaven, a portal or stairway” to that sacred space. For this artist, as for all true believers, it is not about the fleshy fact so much as its transmogrification into the transcendent. “It’s about energy and its transmission,” he explains, “it’s not a predatory gaze but a loving meditation on beauty. It’s all about looking, the asshole and the oculus, looking for love.” [. . .] But so too is it about the power of looking, the awe as registered in the eye. What we do not see, where the sun doesn’t shine and society holds as private as well as somehow shameful, has been excised from our language regarding beauty and the divine. There, unspeakable and out of sight it has far from been out of our mind, buried deep under the social armature of etiquette it has lodged in our collective imagination, slipping out through our bawdy humor—or if you’re Freudian through all manner of pathology—and finding rare voice in a chorus of heretic hymns to this forbidden passage, from the vulgar yet fantastical marginalia drawn by monks on the borders of medieval manuscripts to the preoccupations of Georges Bataille and his L’Anus Solaire.

Christopher Tanner, a total top who finds his salvation through submission to the asshole, has found the heaven above by looking below, the twinkle in an eye that does not blink. Art for him, as with so many before, is a sublimate act of love. Unusual, and perhaps shocking for some, he is not alone in this regard, preceded in a posterior poetics of this inner sanctum by the likes of John Waters’ Twelve Assholes and a Dirty Foot, and a remarkable book by Allen Ginsberg’s longtime lover Peter Orlovsky, Clean Asshole Poems. Sadly overlooked since its publication in 1977 and largely dismissed not just for its subject matter but because Orlovsky’s genius was illiterate, and he couldn’t spell, it is a paean on the order of Tanner’s, and the great beat Gregory Corso’s introduction to the book speaks well to the passion of Tanner’s work:

He hails the human asshole as divine — He offers humankind an anatomical compassion for that bodily part long-maligned, shame-wracked, and poetically neglect. Keep it clean in between is a golden define of self-respect. The angel without wings is with asshole a reality. The angel with wings is a painted thing, a dream. The dual asshole: bucolic and sexual. What comes out, he believes, aught benefit the fields not the seas, aught fertilize not pollute —

What goes in, he lauds as a variable of sex not solely of homosexual kind —

The lovers of callipygian joy are universal.