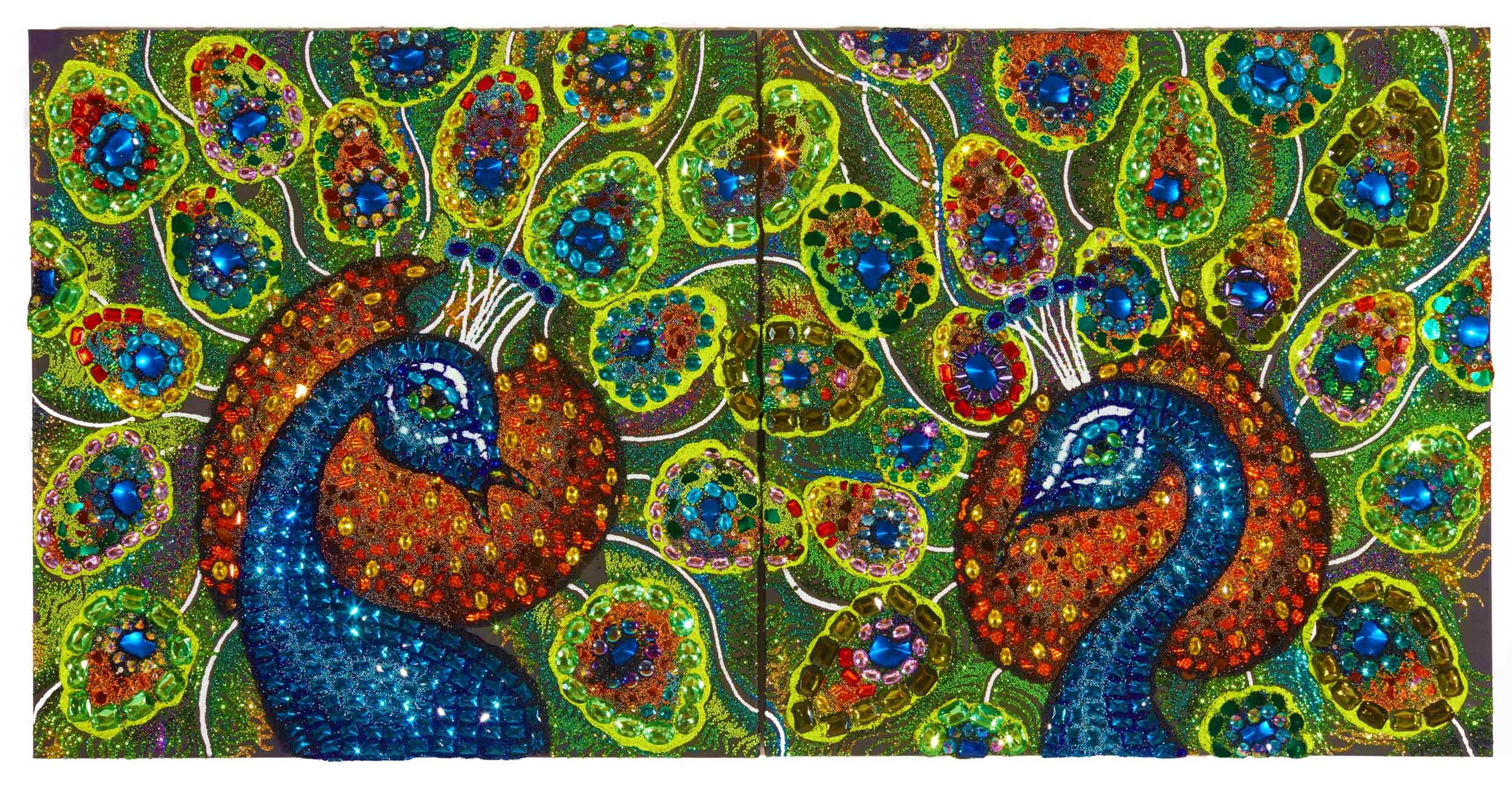

These are your peacocks, Chris, free from historical limitation: fierce, resplendent, decorative, and full of color. You have rendered them in rhinestones, crystals, old German paste, seed beads, shelf paper, glass, tiger eye, polyester glitter, and shells, with acrylic paint holding the mélange together. Their sparkle is blinding. Meticulously, madly, compulsively, wildly, you merge these materials to make two peacocks staring at each other—defying one another with their grandeur

— Robert Kushner

Gates to Paradise

Glitter, paillettes, jewels, beads, minerals and mixed media on canvas

60 x 90 in.

Royal Flush

Glitter, paillettes, jewels, beads, minerals and mixed media on canvas

36 x 72 in.

Royal Flush (Detail)

Paolo

Glitter, paillettes, jewels, beads, minerals and mixed media on canvas

48 x 48 in.

Romeo

Glitter, paillettes, jewels, beads, minerals and mixed media on canvas

72 x 36 in.

Romeo (Detail)

Peacocks per Tutti By Robert Kushner

Moderation is a fatal thing. Nothing succeeds like excess. —Oscar Wilde

Too much of a good thing can be wonderful. —Mae West

Chris Tanner’s latest excesses are definitely too much and are definitely wonderful. In this amazing exhibition covering the entire span of Tanner’s work, two recent diptych paintings of mirrored peacocks steal my heart. These creatures offer a vivid occasion for Tanner to spread his own wings and show off his bricollaging skills, his unique way of creating images out of a diverse array of existing materials.

I have always thought that if Tanner had attended the Bauhaus school, that bastion of reductivist modernism, his over-the-top aesthetic would have withered on the vine. Fortunately, New York’s taste for the overripe gave him a great pool of colleagues and supporters as his unique work emerged and grew.

Peacocks? Allow me to digress. In contrast to the aridity of minimalist presentation, the real school of life for Tanner would have been in Delhi in the 1640s. The Peacock Throne, created for the supreme monarch and aesthete Shah Jahan, was a most impressive object. It took six years to complete and cost more than twice the construction expenses of the Taj Mahal. The French jeweler Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who examined the throne during his sixth voyage to India, described the bejewelled wonder in his 1676 publication Les Six Voyages de J. B. Tavernier:

The underside of the canopy was covered with diamonds and pearls, with a fringe of pearls all round, and above the canopy […] there is to be seen a peacock with elevated tail made of blue sapphires and other coloured stones, the body being of gold inlaid with precious stones, having a large ruby in front of the breast, from whence hangs a pear-shaped pearl of 50 carats or thereabouts, and of a somewhat yellow water. On both sides of the peacock there was a large bouquet of the same height as the bird, and consisting of many kinds of flowers made of gold inlaid with precious stones. On the side of the throne which is opposite the court there is to be seen a jewel consisting of a diamond of from 80 to 90 carats weight, with rubies and emeralds round it, and when the King is seated he has this jewel in full view.

Hello, Chris, we all know you were there.

Or what about James McNeill Whistler’s The Peacock Room (1876), now installed in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Were you on board there too? Fighting peacocks in oil paint and gilding on leather panels…surely you painted the eyes of their feathers.

Let’s forget about the ‘negative press’ that peacocks receive as symbols of pride and vanity. I prefer to think about your peacocks as descendants of the royal birds who strutted their stuff throughout ancient history.

A peacock was the dignified mount of the Hindu god of war Kartikeya, a manly dude if ever there was one. Hera, queen of the Grecian pantheon, had her own peacocks to protect her. Her chariot was pulled by peacocks. That must have been quite a sight. And sound.

Ancient Greeks believed the flesh of peafowl did not decay after death, so the peacock became a symbol of immortality. This symbolism was adopted by early Christians, with many religious paintings and mosaics showing the mythic bird. A peacock drinking from a vase was a symbol of a true believer ingesting the waters of eternal life.

And then, Mr. Tanner, what about your childhood and mine, with the advent of color television? In 1956, we first experienced the daily worship of an abstract eleven-feathered peacock, the ubiquitous and instantlyrecognizable logo for American television broadcaster NBC.

Living peacocks sometimes roamed wild in the San Gabriel Valley suburbs of your childhood and mine, their piercing screams loud enough to wake you out of slumber. Their shedded feathers were sometimes found in the backyard.

These are your peacocks, Chris, free from historical limitation: fierce, resplendent, decorative, and full of color. You have rendered them in rhinestones, crystals, old German paste, seed beads, shelf paper, glass, tiger eye, polyester glitter, and shells, with acrylic paint holding the mélange together. Their sparkle is blinding. Meticulously, madly, compulsively, wildly, you merge these materials to make two peacocks staring at each other—defying one another with their grandeur.

Are they fighting? One with open beak? Are they preening? Or protecting their territory and kin from interlopers? Are they so magnificent they can only be lovers of each other, with no one else remotely worthy? Are they modern evocations of the above iterations? Or is it enough that they are resolutely present, standing defiantly, confident in their encrusted excessiveness?